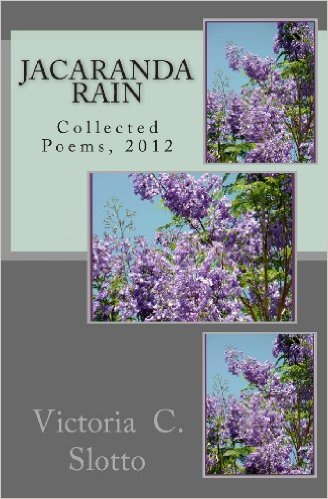

CELEBRATING AMERICAN SHE-POETS (16): Victoria C. Slotto, Jacaranda Rain …

Plain as a needle a poem may be, or opulent as the shell of the channeled whelk, or the ace of the lily, it matters not; it is a ceremony of words, a story, a prayer, an invitation, a flow o words that reaches out and, hopefully, without being real in the way that the least incident is real, is able to stir in the reader a real response.” San Dabs, Seven from Winter Hours by Mary Oliver

Thus begins Victoria C. Slotto’s 2012 poetry collection, Jacaranda Rain, which she dedicated to Oliver “my mentor unaware.” Like Mary Oliver, nature is frequent inspiration for Victoria. The collection includes some fifty-five poems on nature, spirituality, death and dying, which are arranged rather charmingly in alpha order.

What haunts me,” said the dead man

to his wife whose ashes mingled with

his own, “are books I’ve never read –”

from About the Dead Man and Books

“What haunts me more,” the dead man said

for no one else to hear, “are books I never

wrote — ideas fanned to life by life …”

from More About the Dead Man and Books

Victoria certainly will have no such regrets. Since 2009 she’s been publishing her poetry on her blog (Victoria C. Slotto, Author; Fiction, Poetry, Essays). Her original intention in starting the blog was to promote her first novel, Winter Is Past, which was ultimately published by Lucky Bat Books in 2011.

Victoria is however a lover of poetry and was drawn to write and published more and more poetry – Lovely! – becoming involved in poetry groups. (We met via Jingle’s poetry group for those of you who have been around as long as we have and remember that dear lady.)

Victoria eventually became involved with dVerse ~ Poets Pub, “a place for poets and writers to gather to celebrate poetry. We are many voices, but one song. Our goal is to celebrate; poets, verse & the difference it can make in the world. To discover poetry’s many facets and revel in its beauty, even when ugly at times.” dVerse is a collaborative effort offering inspiration, encouragement and education. I highly recommend it, especially if you are just getting started online and want to make connections. Jacaranda Rain includes several poems that were part of an anthology published by dVerse (also recommended). Victoria was for a time a core-team member of The BeZine where she offered monthly prompts for poets and writers.

Victoria’s collection includes explanatory notes for some of the poems and these are engaging and not intrusive.

I dreamt

I flew among the stars

skirted between planets,

cracked open doors

to distant worlds

from Quantum Leaps in Jacaranda Rain

In all since 2009, Victoria has maintained a blog, been an inspiration to poets and a friend to many, written two novels (the second is The Sin of His Father) and a nonfiction book, Beating the Odds: Support for Persons with Early Stage Dementia. Victoria is a former registered nurse who worked primarily with the elderly. She writes from that experience and the more intimate experience of caring for her own mother. As her mother faced early stages of dementia, they worked together to devise practical steps to help her mom remain independent for as long as possible. Victoria offers memory prompts, health care considerations, ideas to help one find meaning in life, suggestions for preparing for the future and more in this very worthy book.

Though I must leave you

I’ll come to you again

a shower of purple petals

on dew covered sod –

from the poem Jacaranda Rain in the collection

Victoria now has a second blog, Be Still and Know That I Am God.

© poem excerpts, book covers/art, and portrait, Victoria C. Slotto

Mary Oliver’s work is deeply rooted in nature and a sense of place, the Ohio of her childhood and the New England of her adult life. More recently Florida, where she moved to be with friends after her partner of forty years died.

Mary Oliver’s work is deeply rooted in nature and a sense of place, the Ohio of her childhood and the New England of her adult life. More recently Florida, where she moved to be with friends after her partner of forty years died.