CELEBRATING AMERICAN SHE POETS (26): May Sarton … when poet becomes woman, “Sisters, My Sisters”

“The creative person, the person who moves from an irrational source of power, has to face the fact that this power antagonizes. Under all the superficial praise of the “creative” is the desire to kill. It is the old war between the mystic and the nonmystic, a war to the death.” May Sarton, Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing

Eleanore Marie Sarton – nom de plume, May Sarton – was born in Ghent in Belgium to an English portrait-artist and interior-designer mother, Mabel Eleanor Elwes, and George Alfred Leon Sarton, a chemist and historian renown as the father of science history.

When the German invasion of Belgium began in August 1914 the family escaped to Mabel Sarton’s mother’s home in Ipswich, England. From there they traveled to America and settled in Boston so George Sarton could teach at Harvard University. May came from a family of gentle nonconformists and her maternal grandfather was among the original Fabians.

“Perhaps every true poem is a dialogue with God … when we are able to write a poem we become for a few hours part of Creation itself.” May Sarton in The Practice of Two Crafts, Christian Science Monitor (1974)

May Sarton’s parents did not belong to any church but she seemed to feel that her parent’s views were not inconsistent with those of the Unitarian Church.

May Sarton’s parents did not belong to any church but she seemed to feel that her parent’s views were not inconsistent with those of the Unitarian Church.

Interviewed in The World in 1987, she told Michael Finley, “My father and mother believed that, though Jesus was not God, he was a mighty leader, and the spirit of Jesus, the logos of him, is the worship of God and the spirit of man.

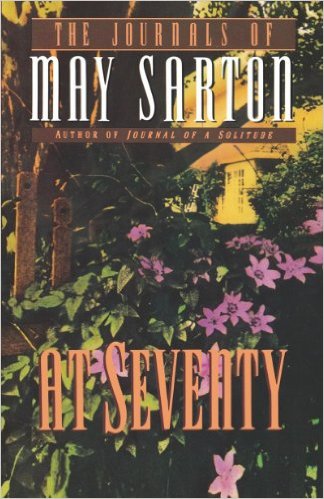

“At the age of ten May was introduced to the Unitarian church by her neighborhood friend Barbara Runkle, whose family attended the First Parish in Cambridge. May was impressed by the minister, Samuel McChord Crothers, whose sermons she thought “full of quiet wisdom.” One sermon in particular, she recalled in her memoir At Seventy, 1984, “made a great impression on me—and really marked me for life. I can hear him saying, ‘Go into the inner chamber of your soul—and shut the door.’ The slight pause after ‘soul’ did it. A revelation to the child who heard it and who never has forgotten it.” The Encyclopedia of Unitarian and Universalist Biography

May began writing early and her first poems – sonnets – were published in Poetry magazine in 1930. Her other love was theatre and she abandoned a scholarship to Vassar to study theatre and to eventually found a theatre company. However, in I Knew a Phoenix, Sketches for an Autobiography she wrote that when her first collection was published she focused on writing and “never looked back.”

Her novel Mrs. Stevens Hears Mermaids Singing is considered a “coming out” book and her work was then labeled lesbian and featured in women’s studies classes. She regretted the label seeing it as limiting, which it is. May Sarton wrote about the experiences, fears and other emotions that are part of being human. Journal of Solitude, for example, is a meditation on aging and the changes aging brings to life, on solitude ( a frequent theme in her work), on love affairs and creativity. May Sarton’s true gifts are poetry and memoir and not to be missed. Her novels – as she knew and admitted – were good but not top-notch.

“Loneliness is the poverty of self; solitude is richness of self.” May Sarton, Journey of Solitude

The following poem, Sisters, My Sisters, is one of May Sarton’s most well know poems. She reads it herself in this video. It was originally published in Kenyon Review in 1943 and is in Selected Poems of May Sarton.

If you are reading this in email, you’ll likely have to link through to the site to view it.

“Nous que voulions poser, image ineffaceable

“Nous que voulions poser, image ineffaceable

Comme un delta divin notre main sur le sable”

– Anna de Noaille

Dorothy Wordsworth, dying, did not want to read,

“I am too busy with my own feelings,” she said.

And all women who have wanted to break out

Of the prison of consciousness to sing or shout

Are strange monsters who renounce the measure

Of their silence for a curious devouring pleasure.

Dickinson, Rossetti, Sappho — they all know it,

Something is lost, strained, unforgiven in the poet.

She abducts from life or like George Sand

Suffers from mortality in an immortal hand,

Loves too much, spends a whole life to discover

She was born a good grandmother, not a good lover.

Too powerful for men: Madame de Stael. Too sensitive:

Madame de Sevigne, who burned where she meant to give

Delicate as that burden was and so supremely lovely,

It was too heavy for her daughter, much too heavy.

Only when she built inward in a fearful isolation

Did any one succeed or learn to fuse emotion

– May Sarton, excerpt from Selected Poems of May Sarton (recommended)

***

“Does anything in nature despair except man? An animal with a foot caught in a trap does not seem to despair. It is too busy trying to survive. It is all closed in, to a kind of still, intense waiting. Is this a key? Keep busy with survival. Imitate the trees. Learn to lose in order to recover, and remember that nothing stays the same for long, not even pain, psychic pain. Sit it out. Let it all pass. Let it go.”

― May Sarton, Journal of a Solitude

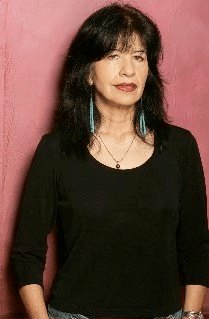

© portrait, Don Cadoret; poem, Sarton estate