Celebrating American She-Poets (15): Sylvia Plath, Listen to the Poet Reading “Ariel”

I can never read all the books I want; I can never be all the people I want and live all the lives I want. I can never train myself in all the skills I want. And why do I want? I want to live and feel all the shades, tones and variations of mental and physical experience possible in my life. And I am horribly limited. Sylvia Plath, “The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath“

What a find! What a treat to hear some of “Ariel” read by its author. So this being the soundbite world of the blogosphere, I simply give you a short bio for those who need one and leave you to the poet herself. Enjoy!

“Sylvia Plath (October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist, and short-story writer. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, she studied at Smith College and Newnham College at the University of Cambridge, before receiving acclaim as a poet and writer. She was married to fellow poet Ted Hughes from 1956 until they separated in September of 1962. They lived together in the United States and then the United Kingdom, and had two children, Frieda and Nicholas. Plath was clinically depressed for most of her adult life. She died by suicide in 1963.

“Plath is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for her two published collections, The Colossus and Other Poems, and Ariel. She also wrote The Bell Jar, a semi-autobiographical novel published shortly before her death. In 1982, she won a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for The Collected Poems.’ Wikipedia

“If neurotic is wanting two mutually exclusive things at one and the same time, then I’m neurotic as hell. I’ll be flying back and forth between one mutually exclusive thing and another for the rest of my days.” Sylvia Plath, “The Bell Jar”

Mary Oliver’s work is deeply rooted in nature and a sense of place, the Ohio of her childhood and the New England of her adult life. More recently Florida, where she moved to be with friends after her partner of forty years died.

Mary Oliver’s work is deeply rooted in nature and a sense of place, the Ohio of her childhood and the New England of her adult life. More recently Florida, where she moved to be with friends after her partner of forty years died.

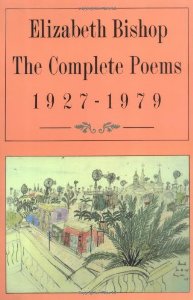

Elizabeth Bishop’

Elizabeth Bishop’