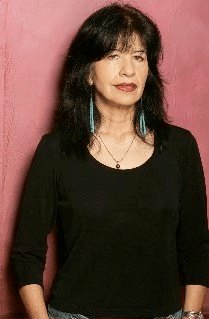

CELEBRATING AMERICAN SHE-POETS (18): Joy Harjo, Crazy Brave

Crazy Brave (Norton & Company, 2012), Joy Harjo’s eminently engaging memoir, flows like a long prose poem. It is rich and well-built on a foundation of tribal mythologies, a strong sense of her ancestry, her difficult childhood and youth and salvation found in poetry and music. From her birth to a handsome much-loved fire-spirit father who inherited Indian oil money, allowing him to indulge a passion for cars, and her beautiful water-spirit singer-mother whose voice was stilled by a bully of a second-husband, Harjo tells the story of girl who survived a physically and emotionally abusive step-father, crushing poverty and the greater cultural obscenities to become one of our most influential poets and a formidable advocate for justice for Native Americans and liberation for women.

I was entrusted with carrying voices, songs, and stories to grow and release into the world, to be of assistance and inspiration. These were my responsibility.”

*****

I can’t imagine the human being who wouldn’t relate to Joy Harjo’s history, but those who have come from “broken” homes, poverty and a family of mixed ethnicity will most especially appreciate it and perhaps find some healing and strength in the pages of Crazy Brave. That Joy Harjo survived so much to become a decent loving person leaves the rest of us with no excuse; and any writer, poet or musician will take to heart the dreams and visions of that long journey to find hope and creative voice in poetry.

Joy Harjo, a member of the Mvskoke tribe was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, an area where the Native American trail of tears ended, an area to which the indigenous peoples were removed – forced to relocate – as people of European descent moved into their original home places. The removed were the Five Civilized Tribes – Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Mvkoke and Seminole – who were living as autonomous nations in what is now the American Deep South.

“I fought through the War Between the States and have seen many men shot, but the Cherokee Removal was the cruelest work I ever knew”. Georgian soldier who participated in the removal

*****

When the World as We Knew It Ended

It was coming.

We had been watching since the eve of the missionaries in their long

and solemn clothes, to see what would happen.

We saw it

from the kitchen window over the sink

as we made coffee, cooked rice and potatoes

enough for an army.

We saw it all, as we changed diapers and fed

the babies. We saw it,

through the branches of the knowledgeable tree,

through the snags of stars, through

the sun and storms, from our knees

as we bathed and washed the floors …

The conference of the birds warned us as they flew over

destroyers in the harbor, parked there since the first takeover.

It was by their songs and talk we knew when to rise,

when to look out the windowexcerpt from When the World Ended in How We Became Human, New and Selected Poems (W.W. Norton & Co., 2004)

*****

Joy Harjo’s poetry and music are influenced by her ethnic heritage and her feminist and social concerns as well as by her love of word and sound and her education in the arts. Largely autobiographical, her poetry is informed with descriptions of the Southwestern landscape and the mythologies, symbols and values of the Mvskoke people. Hers is the sort of writing that sits with you to become part of your own bone and marrow, which is the way of good poetry and good story. A poet of the people but also a critically-acclaimed poet, her many awards include the Wallace Stevens Award of the Academy of American Poets, The William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America and the American Indian Distinguished Achiement in the Arts Award. She is the recipient of several grants and is a teacher, musician (saxophone) and singer. She has published some fourteen books and ten music albums.

It was a dance,

her back against the wall

at Carmen’s party. He was alone

and he called to her – come here, come here

that was the firs time she saw him

and later she and Carmen drove him home

and all the way he talked to the moon,

to the stars, to someone ridingexcerpt from There Was a Dance, Sweetheart in How We Became Human: New and Selected Poems (1975-2022) (W.W. Norton & Co., 2004) © Joy Harjo

If you are reading this post from email, you will likely have to link though to this blog to enjoy the video. Joy Harjo’s Eagle Song, poem and music:

© review, Jamie Dedes; poems, Joy Harjo, photographs courtesy of Ms Harjo

Mary Oliver’s work is deeply rooted in nature and a sense of place, the Ohio of her childhood and the New England of her adult life. More recently Florida, where she moved to be with friends after her partner of forty years died.

Mary Oliver’s work is deeply rooted in nature and a sense of place, the Ohio of her childhood and the New England of her adult life. More recently Florida, where she moved to be with friends after her partner of forty years died.