NOTIONS OF THE SACRED: Poetry as Spritual Practice

“Without art, we should have no notion of the sacred; without science, we should always worship false gods.” W.H. Auden

Originally published d in The BeZine.

When we move on in the arc of our lives – to center – we cross the threshold into that place from which all things emanate – the sacred space of poetry and indeed all art and creativity. We leave behind the cacophony of assumptions and received wisdom to rest in Rumi’s field – a place he says is “beyond ideas of wrong doing and right doing.” We cross the threshold into a w-h-o-l-l-y, place – a place Rumi tells us the “world is too full to talk about.” The ideal of this field reminds me very much of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, where all the hallelujah’s – broken or whole – are equal. And so it is with us and with our poetry, which as a spiritual practice brings balance and sacredness into our lives.

This business of taking up our pens involves more than learning the technical rudiments, the history of our craft and its key players. It requires of us a trust in ourselves. It requires letting go of the expectation of understanding everything. We learn to embrace mystery and ambiguity. We learn to sit with process and to sit with the poems we are drawn to or the poetry we write . . . or, perhaps which writes us. We allow the visions, the word-play, the colors, tones and cadence to work on us. Whether we share our poems with others or not, whether we are amateur or professional, is irrelevant. What matters is that we go on the hero’s journey and we come back with a gift.

When we write, we are like Rilke’s “Swan” …

“when he nervously lets himself down

into the water, which receives him gaily

and which flows joyfully under

and after him, wave after wave,

while the swan, unmoving and marvelously calm,

is pleased to be carried, each moment more fully grown,

more like a king, further and further on.”

Sacred space always reveals the unexpected. We are always changed, though the change may be subtle. What might come up are the daily concerns – how to make it through the day – or the current pain: the loss of a loved one, abandonment, ills of body and mind, concerns for children … Joy! and Gratitude! As we grow “more like a king, further and further on,” our sacred space may reveal something about the greater mysteries…

“does it matter after all, the curiosities

when fish and water are one

when light and dark are indistinguishable

when we are neither content nor discontent

when questions cease and ideologies melt

when there is no helping and no taking

. . . there is this” [© Jamie Dedes]

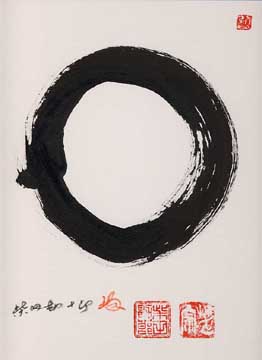

And “this” is well represented by the Buddhist ensō illustrated above. It is meant to express that moment when the mind is still, allowing for creation. It symbolizes enlightenment. I’m sure all faiths have similar concepts. From a Christian perspective – perhaps the discussion would be about the “gaze of faith” and claritas (Thomas Aquinas) – “intellectual light,” illumination. In Buddhism, traditionally this ensō is done as a part of spiritual practice and it is a kind of meditation in the way that all creative efforts are meditation.

“Writing is a process in which we discover what lives in us. The writing itself reveals to us what is alive in us. The deepest satisfaction of writing is precisely that it opens up new spaces within us of which we were not aware before we started to write. To write is to embark on a journey whose final destination we do not know. Thus, writing requires a real act of trust. We have to say to ourselves: ‘I do not yet know what I carry in my heart, but I trust that it will emerge as I write.’ Writing is like giving away the few loaves and fishes one has, trusting that they will multiply in the giving. Once we dare to ‘give away’ on paper the few thoughts that come to us, we start discovering how much is hidden underneath these thoughts and gradually come in touch with our own riches.” Henri Nouwen REFLECTIONS ON THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION (unpublished) http://www.henrinouwen.org

So trust that through your poetry you will enter that field where there is no right doing or wrong doing and …

“The time will come

when, with elation

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror

and each will smile at the other’s welcome,

and say, sit here. Eat.

You will love again the stranger who was your self.

Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart

to itself, to the stranger who has loved you

all your life, whom you ignored

for another, who knows you by heart.

Take down the love letters from the bookshelf,

the photographs, the desperate notes,

peel your own image from the mirror.

Sit. Feast on your life. “ [Love After Love, © Derrick Walcott, Collected Poems, 1948–1984 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1987)

© 2016, essay and photograph, Jamie Dedes, All rights reserved; Ensō (c. 2000) by Kanjuro Shibata XX under CC BY-SA 3.0