The BeZine, October 2017, Vol. 4, Issue 1, Music to the Eyes

October 15, 2017

” After silence, that which comes nearest to expressing the inexpressible is music ”

~ Aldous Huxley

Reading Michael Dickel’s introduction to last month’s edition of The BeZine, sowing the seeds of the mindset at the roots of the ethos of this publication – promoting peace, sustainability and social justice – but in particular, overcoming anger and harnessing it for good, he quotes a good deal of Audre Lorde’s laudable speech and essay The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism, perhaps a reflection on what divides the world, what creates so much anxiety, political division, protective greed and selfishness.

So, we have music.

I don’t know about you, but there are few times in my life when music has done anything other than have a life enhancing and positive effect on me – with the possible exception of a Moody Blues concert I went to in 1969, in my university days, when I was left with a ringing in my ears for several days. This was, along with competitive shooting of Lee-Enfield .303 bore rifles at school, without ear defenders, probably the root of my tinnitus! Subsequently, I carry ear plugs and try to avoid over amplified performances by groups of musicians, who employ sound engineers, who may be – shall we say – aurally challenged!

Music, particularly live and acoustic music has played and still does play an increasingly major part in most of my life; it provides a therapy against the rigours and stresses of everyday living. But it does more than this.

My personal perspective on the value of poetry has some relevance here. It is a belief that poetry should always be one step removed from the obvious, the logical and rational, in order for it to awaken the right brain, the creative side of our amazing abilities as humans; to stimulate the visceral (as opposed to the purely intellectual, rational, ‘logical’) response. In turn, this has the potential to stimulate a fresh approach to solving the challenges, be they personal or global. This hits on the core mission of The BeZine in a big way.

But if poetry has this potential power to stimulate a new way of thinking outside the framework imposed by a culture of consumerism, greed and material comfort, as opposed to our social well being, then music does so with a vengeance. It is truly visceral without the constraints of language. Of course, when the poetry of lyrics is introduced to create song, then there is the opportunity to create something that is greater than the sum of its parts; synergy. It can provide something that dwells in the conscious and even subconscious for a lifetime – whoever forgets the words and melody of a song that they heard at a very poignant moment in their lives, which continues to inhabit a special place in memory, resonate and invoke the most emotional response every time it is heard. There are a few who would argue this is ‘just an over-emotional response’, but it may well be the last resort for understanding and developing the insight to the human need for compassion as well as passion in our lives.

But if poetry has this potential power to stimulate a new way of thinking outside the framework imposed by a culture of consumerism, greed and material comfort, as opposed to our social well being, then music does so with a vengeance. It is truly visceral without the constraints of language. Of course, when the poetry of lyrics is introduced to create song, then there is the opportunity to create something that is greater than the sum of its parts; synergy. It can provide something that dwells in the conscious and even subconscious for a lifetime – whoever forgets the words and melody of a song that they heard at a very poignant moment in their lives, which continues to inhabit a special place in memory, resonate and invoke the most emotional response every time it is heard. There are a few who would argue this is ‘just an over-emotional response’, but it may well be the last resort for understanding and developing the insight to the human need for compassion as well as passion in our lives.

“If music be the food of love, play on;” said Duke Orsino “give me excess of it”. The opening lines of Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night” speaks much for music, even though he goes on, cynically “that, surfeiting, the appetite may sicken, and so die”. Can you get too much of a good thing, I ask?

Music is so often a catalyst for romance. We could not even begin to count the number of songs that have ever been written over the ages on the subject of romantic or divine and spiritual love … and its consequences. However, I wonder how often we may contemplate how many instrumental or orchestral compositions there are, which, without words, in a different way, on a very different level, are capable of promoting a feeling of love and, equally, a sense of calm, peace, remorse, sadness, melancholy, a whole gamut of emotional responses that can and very often do bring about a state of mind that is elevated above the daily grind of our lives, the trauma, the tragedies, the disasters and injustices we witness every day in the news, and above all, the ability it has to help us cry. In this way, music can act as a protest against injustice and, in a sense, be ‘angry’, but still it can act as a relief for that anger, just as poets can find simply by writing a ‘political’ poem, which can relieve the frustration and anxiety brought about by political injustice. It is this value that I attach to music that I hold highest in my personal esteem for this art of arts.

Music is so often a catalyst for romance. We could not even begin to count the number of songs that have ever been written over the ages on the subject of romantic or divine and spiritual love … and its consequences. However, I wonder how often we may contemplate how many instrumental or orchestral compositions there are, which, without words, in a different way, on a very different level, are capable of promoting a feeling of love and, equally, a sense of calm, peace, remorse, sadness, melancholy, a whole gamut of emotional responses that can and very often do bring about a state of mind that is elevated above the daily grind of our lives, the trauma, the tragedies, the disasters and injustices we witness every day in the news, and above all, the ability it has to help us cry. In this way, music can act as a protest against injustice and, in a sense, be ‘angry’, but still it can act as a relief for that anger, just as poets can find simply by writing a ‘political’ poem, which can relieve the frustration and anxiety brought about by political injustice. It is this value that I attach to music that I hold highest in my personal esteem for this art of arts.

It is, in fact, an art that can, like no other, combine the poetry of good lyrics, the rhythms of our roots, the vast array of instrumental sounds and voices, and the spine tingling harmonies they can create, into one; that can team itself with other art forms, particularly in photography, film and dance, but also notably in storytelling. What broadcast programme, be it documentary, drama, comedy, film (movie) is made without serious thought for the addition of music, a song, an orchestral piece, which so often includes a main theme along with incidental ‘tracks’ throughout its production, which then, of course, naturally leads to the merchandising of a soundtrack album.

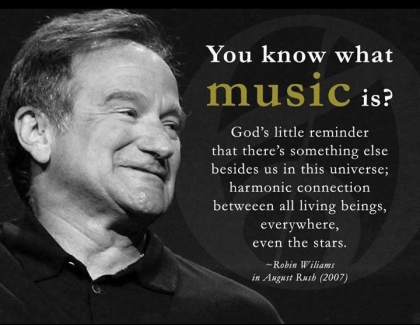

Even the latest generation of advertisers have realised the visceral value of music, sometimes combined with poetry (look at Apple’s poetic narration by the inimitable and dearly missed Robin Williams, who significantly quoted from Walt Whitman’s poem O Me, O Life to evoke the kind of emotional responses that are known to drive most human decisions … in this case, to buy!

As a test of how important a part music plays in teasing our wallets from our pockets, next time such an advert hits your screen, try turning off the sound. What are you left with … not a lot that is meaningful. Now here, I hope the photographers and cinematographers amongst us (Naomi Baltuck) will not take exception to this notion that still and moving pictures cannot move us, which of course they can and a similar thesis to this could be written for the visceral value of great pictures, but I know you will trust that my meaning, in this context, is well intended!

This month, as lead editor for the anniversary edition of The BeZine, the first of its fifth year, we feel quite frankly blessed with the quantity and quality of contributions we have received from our regular core contributors, and I take my hat off to our new guest contributors, including some very talented young writers and musicians. The sizeable response of quality submissions makes this, I believe, our largest issue yet; like a big fat magazine, but without any adverts, in itself, says something about the importance we attach to music.

We have poems galore, almost all of which touch the music theme or contain subtle references to it. Two fellow Brits are amongst the new contributors to The BeZine. From musician and composer, Joseph Alen Shaw, a piece that addresses the core of the Bardo Group Bequines mission, Music Beyond Belief, on the subject of faith and musical composition in the 20th Century. Joseph has also contributed another account of one of his recent compositions, the Wentworth Cantata. British newcomer, historian and musician, Emily Needle, has written an account of her research on her travels through Eastern USA in 2005, into the achievements of a remarkable and little known Charleston man, who had a surprisingly big influence on Jazz music in the early 20th Century.

We have poems galore, almost all of which touch the music theme or contain subtle references to it. Two fellow Brits are amongst the new contributors to The BeZine. From musician and composer, Joseph Alen Shaw, a piece that addresses the core of the Bardo Group Bequines mission, Music Beyond Belief, on the subject of faith and musical composition in the 20th Century. Joseph has also contributed another account of one of his recent compositions, the Wentworth Cantata. British newcomer, historian and musician, Emily Needle, has written an account of her research on her travels through Eastern USA in 2005, into the achievements of a remarkable and little known Charleston man, who had a surprisingly big influence on Jazz music in the early 20th Century.

Beside Joseph and Emily, other new contributors have all embraced the music theme in such creative ways, mostly poetry but also some lyrical prose, with very interesting results. Stephanie Williams’ Singing Man is a charming prose piece that evokes a child’s certain view of what they like. S.R. Chappell has written a couple of poems in praise of music. Kakali Das Ghosh, in her poem, presents us with some very mystical feelings. Andrew Scott gives us a story of a gritty performer with all the emotional baggage that can accompany that way of life, and JB Mulligan writes three deeply insightful and thought provoking poems.

All of our regular contributors have also given us a wealth of musical delight and I thank them all for their excellence that has made this issue very special.

Further Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Glen Armstrong (his deeply nostalgic plea for vinyl records that ‘once had purpose’), Naomi Baltuck (for your photo essay with a family musical conclusion), Sonja Benskin Mesher (her beautiful reflective on ageing, remembering, companionship ends with music), Paul Brookes (fine poems, particularly clever is his onomatopoeic on a Bodhrán), Miki Byrne (whose poems about performance are both clever and revealing), Bill Cushing (and his handful of poems with oh so subtle musical references), Jamie Dedes (whose Orchestra of Impossible Beauty relates the moving story of the British ‘ParaOrchestra’ comprised of people with a variety of disabled conditions), Renee Espriu (and who can resist the image of how a child can hear the recording in a seashell of the sound of the sea or how they can bring home from school a musical instrument that’s bigger than themselves!), Denise Fletcher (on a trip to a Country Music Festival or the intrusive quality of loud music), Priscilla Galasso (for her usual insightful qualities), Mike Gallagher (for his remarkable, lyrical prose piece), Mark Heathcote (and his Whispering Muse), Charles Martin (and his ekphrastic haiku / senryu triplet), Liliana Negoi (for super imaginative variety of expression), Phillip Stephens (with a further challenging ekphrastic poem), John Sullivan (whose poems include a conversation with his radio, deeply embedded with the blues and a call to the Tripitaka of Buddhism), Lynn White (for not allowing us to forget the importance in our lives of birdsong), and the artful collaboration of photograph Amy Bassin and poet Mark Blickley in Screaming Mime.

So much delight from each and every one of our writers, I can’t tell you what a pleasure this has been, to write about one of my favourite pastimes.

Enjoy.

John Anstie, Contributing Editor and Team Leader for the Music Issue

Illustrations are courtesy of From: ‘Notable Quotes’ hand carved code

THANK YOU!

It seems somehow right that we dance into our fifth year on a musical note and John’s perceptive and passionate introduction to this month’s The BeZine. It is no exaggeration to say that the longevity of this 100% volunteer effort is the outgrowth of the stalwart support of readers and contributors and the work, creativity, vision and perspicacity of our core team: John Anstie, Naomi Baltuck, James R. Cowles, Michael Dickel, Priscilla Galasso, Chrysty Hendrick, Joseph Hesch, Ruth Jewel, Charlie Martin, Liliana Negoi, Lana Phillips, Corina Ravenscraft ,Terri Stewart (founder of Beguine Again, our sister site), and Michael Watson.

It seems somehow right that we dance into our fifth year on a musical note and John’s perceptive and passionate introduction to this month’s The BeZine. It is no exaggeration to say that the longevity of this 100% volunteer effort is the outgrowth of the stalwart support of readers and contributors and the work, creativity, vision and perspicacity of our core team: John Anstie, Naomi Baltuck, James R. Cowles, Michael Dickel, Priscilla Galasso, Chrysty Hendrick, Joseph Hesch, Ruth Jewel, Charlie Martin, Liliana Negoi, Lana Phillips, Corina Ravenscraft ,Terri Stewart (founder of Beguine Again, our sister site), and Michael Watson.

There are so many other ways readers, contributors and team could choose to spend valuable time, but you have all chosen to invest a portion in this small effort to build a community of others.

This site was founded in 2011 with three American Buddhist friends. Two have passed on. Since that time as both blog and zine we have published the works of like-minded representing all races, at least six religions, agnosticism and atheism and, I believe, nearly thirty countries. We have stood in solidarity for kindness and joy and raised our voices for peace, environmental sustainability and social justice.

HAPPY ANNIVERSARY to all of us. Thank you everyone and may peace and friendship prevail.

On behalf of the Bardo Group Beguines

and in the spirit of peace, love (respect) and community,

Jamie Dedes

Managing Editor

MUSIC TO THE EYES

How to read this issue of THE BeZINE:

Click HERE to read the entire magazine by scrolling, or

You can read each piece individually by clicking the links in the Table of Contents.

To learn more about our guests contributors, please link HERE.

To learn more about our core team members, please link HERE.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Poetic Musical Musings

Underneath The Stairs, John Anstie

Cannonball Adderley Adrift, Glen Armstrong

Post-Punk, Glen Armstrong

Used Records, Glen Armstrong

Under A Rainbow. Somewhere., Mendes Benito

First Time, Paul Brookes

Bodhrán, Paul Brookes

When I Used to Play, Miki Byrne

Beginners Night, Mike Byrne

Applause, Miki Byrne

For Gilly Dangerous, Miki Byrne

Music Crashing, S.R. Chappell

Music Within, S.R. Chappell

Ode to Nina Simone, Bill Cushing

On Modest Mussourgsky’s “Bydlo”, Bill Cushing

La Rosa & El Dragon (impressions from the music of “Pan’s Labyrinth”, Bill Cushing

“Zooz’s Brasshouse” Busking, Bill Cushing

Blakeson, Bill Cushing

Harmonic Chanson, Kakali Das Ghosh

The Music of the Conch Shell, Renee Espriu

The Music of Prowess, Renee Espriu

Intrusion, Denise Fletcher

The Whisper of the Muse, Mark Heathcote

Three Notes, Charles Martin

As We Go Together, Sonja Benskin Mesher

String Quartet, JB Mulligan

Consolation #3 in D Flat by Liszt, JB Mulligan

Canon, JB Mulligan

Song for Agriope, Liliana Negoi

Feathery Song, Liliana Negoi

Mr. Bluesman, Andrew Scott

Understanding the Flautist (Meditation on a Peace Painting), Phillip T. Stephens

Llano Estacado, John Sullivan

True Emergency, John Sullivan

Aubade on Royal Street, John Sullivan

Chill, Lynn White

To The Passing of The Nightingale,Lynn White

~~~~~~~

Musical Insights

Press Play, Photo Essay from Naomi Baltuck

How Hawkwind Improved My Adolescence, Paul Brookes

A Christmas Reflection On Skepticism and A Confession, James R Cowles

Country Music, Cow Pokes and City Girls, Jamie Dedes

The Orchestra of Impossible Beauty, Jamie Dedes

Stars In My Eyes, Denise Fletcher

Beyond Music Appreciation, Priscilla Galasso

The Clonmel Set, Mike Gallagher

From Rags Through Race to Ragtime, Emily Needle

The Presence of Sound, Liliana Negoi

Music Beyond Belief, Joseph Alen Shaw

The Singing Man, Stephanie Williams

~~~~~~~

Music, Video & Special Interest

My (Sort of) Desert Island Discs, John Anstie

Wentworth Cantata, Joseph Alen Shaw

Screaming Mime, Amy Bassin and Mark Blickley

Stocksbridge Memorial Project, Ian McMillan

Translating Words Into/From Music, Liliana Negoi

Except where otherwise noted,

ALL works in The BeZine ©2017 by the author / creator

CONNECT WITH US

The BeZine: Be Inspired, Be Creative, Be Peace, Be (the subscription feature is below and to your left.)

Daily Spiritual Practice: Beguine Again, a community of Like-Minded People

Facebook, The Bardo Group Beguines

Twitter, The Bardo Group Beguines

Submissions:

Read Info/Missions Statement, Submission Guidelines, and at least one issue before you submit. Updates on Calls for Submissions and other activities are posted every Sunday in Sunday Announcements on The Poet by Day.